Buried on Page 86 of Stopgap Spending Bill: Congress Extends Pandemic Emergency Powers, Biodefense Secrecy, and Pharma Privileges Through September 2025

Congress looks to extend emergency powers and secrecy over high-containment laboratories in stopgap funding bill.

Tucked inside Congress’ latest stopgap funding bill is something far more dangerous than temporary government spending. Lawmakers have quietly extended dozens of federal emergency powers and programs that were originally set to expire this month—extending them through September 30, 2025.

The U.S. House of Representatives is voting on this bill today.

These laws give the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) and other top federal officials sweeping, unilateral powers over the American people in the event of a declared—or even a potential—public health emergency. Under these authorities, the federal government can declare emergencies, deploy federalized medical teams, lock down communities, roll out mass vaccination campaigns, and fast-track the use of unlicensed drugs and vaccines. Even state personnel can be reassigned to serve federal priorities.

Congress didn’t just extend emergency powers. Lawmakers also renewed legal authority for total secrecy over government-funded pandemic research, countermeasure development, and the activities of high-containment biolabs working with dangerous pathogens. Americans will remain locked out of knowing where these labs are, what viruses they’re working on, and how vulnerable the nation’s defenses really are.

And if that wasn’t enough, Congress re-upped special antitrust exemptions that allow Big Pharma and government agencies to coordinate in secret on the manufacture, distribution, and stockpiling of pandemic countermeasures—without any public oversight and without the usual competition laws that prevent monopolies.

These laws weren’t passed during a national emergency. They weren’t rushed through during a new pandemic. Congress extended them as part of a temporary funding measure—a 99-page continuing resolution designed to keep the government’s lights on. And buried in the fine print were provisions that give unelected bureaucrats sweeping powers over your life, your health, and your freedom.

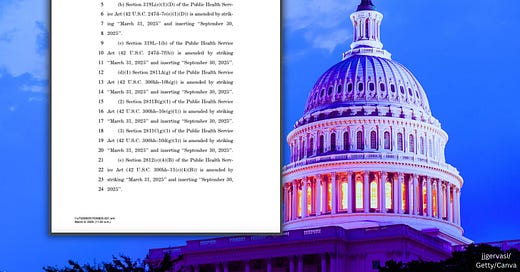

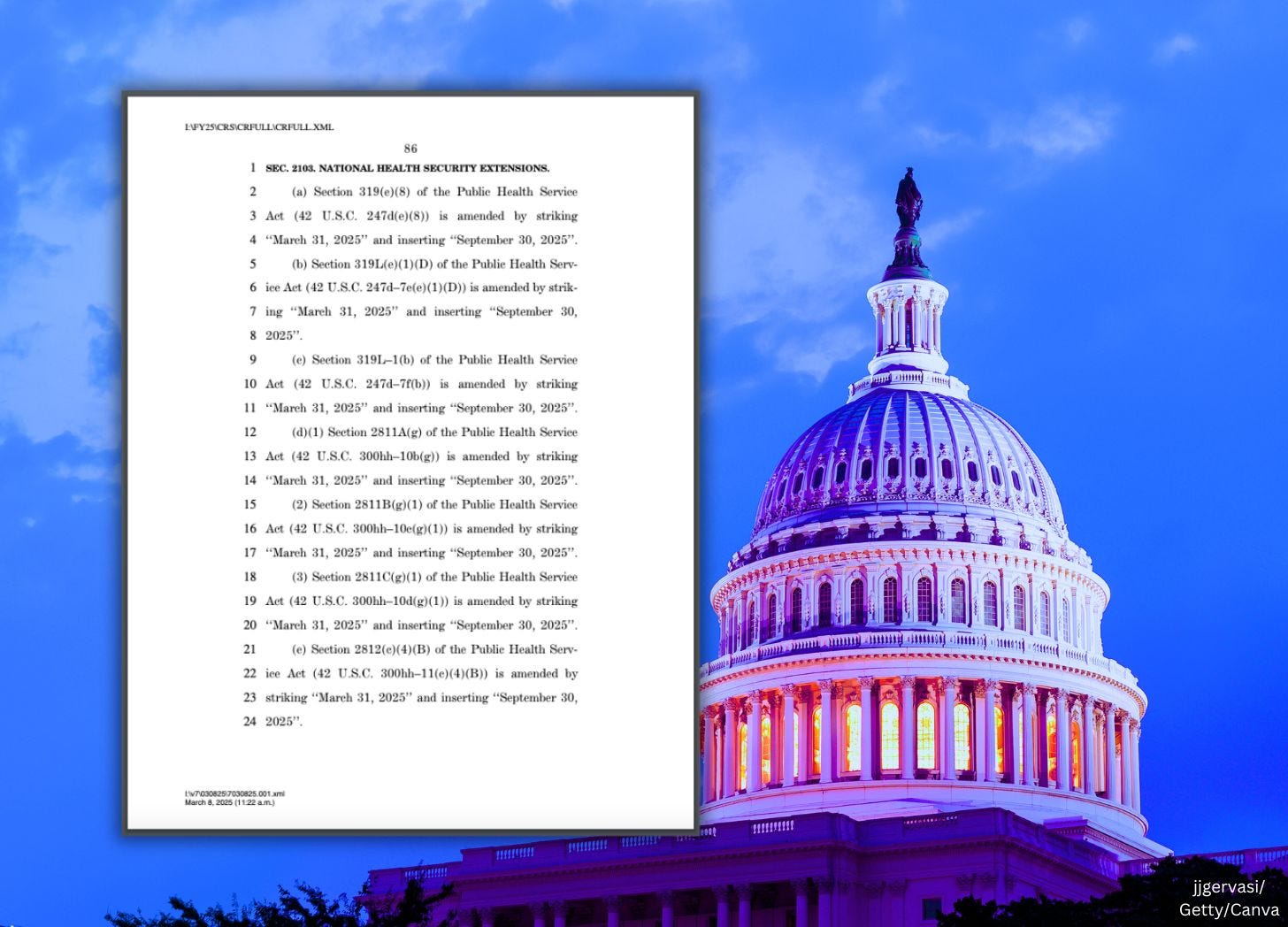

They buried all of this in dense legalese—referencing the Public Health Service Act (here)—on page 86 of the continuing resolution stopgap bill.

This article breaks down each section of these extended laws—using direct quotes from the legislation itself—to show exactly what Congress just did, how it impacts you, and why every American should be asking serious questions.

Follow Jon Fleetwood: Instagram @realjonfleetwood / Twitter @JonMFleetwood / Facebook @realjonfleetwood

Section 319(e) of the Public Health Service Act—Extended Emergency Powers

Congress extended Section 319(e) of the Public Health Service Act through September 30, 2025, giving the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) expanded authority during declared public health emergencies.

Under this law, the Secretary can declare a public health emergency, and with that declaration, unlock sweeping federal powers.

The law states:

“If the Secretary determines, after consultation with such public health officials as may be necessary, that—

(1) a disease or disorder presents a public health emergency; or

(2) a public health emergency, including significant outbreaks of infectious diseases or bioterrorist attacks, otherwise exists,

the Secretary may take such action as may be appropriate to respond to the public health emergency, including making grants, providing awards for expenses, and entering into contracts and conducting and supporting investigations into the cause, treatment, or prevention of a disease or disorder.”

(Sec. 319(a), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 96)

This declaration can be renewed indefinitely, allowing the Secretary to extend emergency powers beyond the initial 90-day limit:

“Determinations that terminate under the preceding sentence may be renewed by the Secretary (on the basis of the same or additional facts), and the preceding sentence applies to each such renewal.”

(p. 96)

Once a public health emergency is declared, the Public Health Emergency Fund becomes available with no fiscal year limitations:

“There is established in the Treasury a fund to be designated as the ‘Public Health Emergency Fund’ to be made available to the Secretary without fiscal year limitation to carry out subsection (a).”

(Sec. 319(b)(1), p. 96)

The Secretary can use this fund to:

“Facilitate and accelerate, as applicable, advanced research and development of security countermeasures... or qualified pandemic or epidemic products... strengthen biosurveillance capabilities... support the initial deployment and distribution of contents of the Strategic National Stockpile... and carry out other activities, as the Secretary determines applicable and appropriate.”

(Sec. 319(b)(2), p. 97)

It also gives the Secretary the ability to waive reporting requirements and deadlines for individuals and entities affected by the emergency:

“The Secretary may, notwithstanding any other provision of law, grant such extensions of such deadlines as the circumstances reasonably require, and may waive, wholly or partially, any sanctions otherwise applicable to such failure to comply.”

(Sec. 319(d), p. 97)

Lastly, it permits the temporary reassignment of state and local personnel funded through federal programs:

“Upon request by the Governor of a State or a tribal organization or such Governor or tribal organization’s designee, the Secretary may authorize the requesting State or Indian tribe to temporarily reassign, for purposes of immediately addressing a public health emergency in the State or Indian tribe, State and local public health department or agency personnel funded in whole or in part through programs authorized under this Act, as appropriate.”

(Sec. 319(e)(1), p. 98)

This section of law lays the foundation for declaring emergencies, authorizing emergency use products, deploying countermeasures, and reassigning personnel—and Congress has now extended it through September 30, 2025.

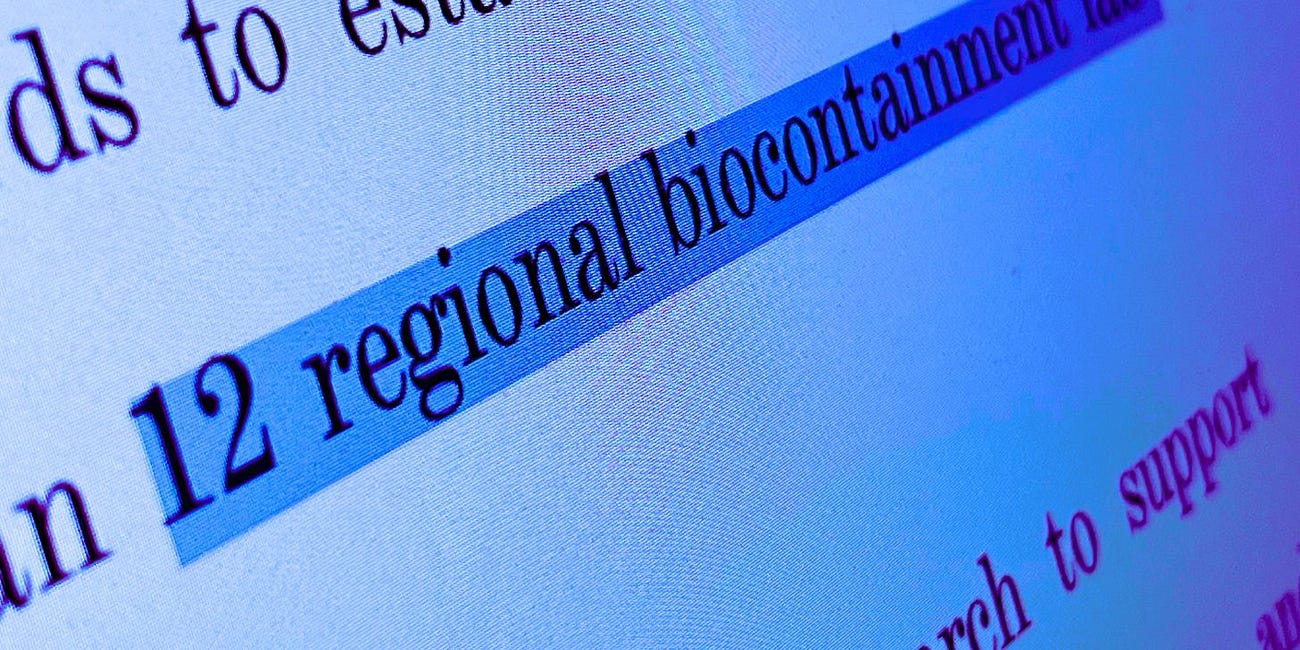

Section 319L(e)(1)(D) of the Public Health Service Act—Extended Secrecy Over Federally Funded Biodefense Programs

Congress extended Section 319L(e)(1)(D) of the Public Health Service Act through September 30, 2025. This section gives the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) the authority to conceal information from the American public about federally funded medical countermeasure programs, high-containment laboratory activities, and security assessments. These nondisclosure powers were originally set to expire on March 31, 2025, but Congress has now extended them for another six months.

Under this law, HHS can block public access to critical information about the government’s research and development of vaccines, drugs, and other so-called “countermeasures.” It also allows HHS to keep secret the operations of high-containment laboratories working with dangerous pathogens, as well as government assessments of the nation’s vulnerabilities to chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear threats.

The law states:

“In general.—Information described in clause (ii) shall be deemed to be information described in section 552(b)(3) of title 5, United States Code.”

(Sec. 319L(e)(1)(A)(i), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 198)

This designation means the information is exempt from disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). In other words, Americans have no legal right to access it.

The law describes what HHS is allowed to keep hidden:

“The information described in this clause is information relevant to programs of the Department of Health and Human Services that could compromise national security and reveal significant and not otherwise publicly known vulnerabilities of existing medical or public health defenses against chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear threats, and is comprised of—

(I) specific technical data or scientific information that is created or obtained during the countermeasure and product advanced research and development carried out under subsection (c);

(II) information pertaining to the location security, personnel, and research materials and methods of high-containment laboratories conducting research with select agents, toxins, or other agents with a material threat determination under section 319F–2(c)(2); or

(III) security and vulnerability assessments.”

(Sec. 319L(e)(1)(A)(ii), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, pp. 198–199)

This means the public cannot see the scientific data from federally funded biodefense research, cannot know the locations or operations of high-containment labs working with potentially pandemic pathogens, and cannot review government assessments of the country’s weaknesses in biosecurity.

The law requires HHS to review its decision to withhold this information only once every five years, unless the Secretary decides to do it sooner:

“Information subject to nondisclosure under subparagraph (A) shall be reviewed by the Secretary every 5 years, or more frequently as determined necessary by the Secretary, to determine the relevance or necessity of continued nondisclosure.”

(Sec. 319L(e)(1)(B), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 199)

The law does not require an independent review or any public disclosure of what information is being withheld or why.

HHS is required to submit an annual report to Congress, but the report includes only the number of times it withheld information—there is no requirement to reveal the specific nature of the information being concealed:

“One year after the date of enactment of the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness and Advancing Innovation Act of 2019, and annually thereafter, the Secretary shall report to the Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions of the Senate and the Committee on Energy and Commerce of the House of Representatives on the number of instances in which the Secretary has used the authority under this subsection to withhold information from disclosure, as well as the nature of any request under section 552 of title 5, United States Code that was denied using such authority.”

(Sec. 319L(e)(1)(C), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 199)

This section of law allows the federal government to operate significant parts of its publicly funded pandemic preparedness and biodefense programs in complete secrecy. Congress has now extended these nondisclosure powers through September 30, 2025.

Section 319L–1(b) of the Public Health Service Act—Extended Antitrust Exemptions for Countermeasure Collaborations

Congress extended Section 319L–1(b) of the Public Health Service Act through September 30, 2025. This section grants the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), along with the Attorney General and the Secretary of Homeland Security, broad authority to coordinate meetings and establish agreements between private pharmaceutical companies and government agencies for the development, manufacturing, and distribution of medical countermeasures, including vaccines and drugs. The law specifically provides exemptions from federal antitrust laws, allowing these entities to collaborate without the usual legal restrictions that prevent anti-competitive behavior.

Under this law, private companies working on federally designated countermeasures are permitted to meet, consult, and enter into agreements under the direct supervision of HHS, without fear of antitrust violations. These meetings and agreements can be initiated by the government or by private industry and are explicitly shielded from public disclosure.

The law states:

“The Secretary, in coordination with the Attorney General and the Secretary of Homeland Security, may conduct meetings and consultations with persons engaged in the development of a security countermeasure (as defined in section 319F-2), a qualified countermeasure (as defined in section 319F-1), or a qualified pandemic or epidemic product (as defined in section 319F-3) for the purpose of the development, manufacture, distribution, purchase, or storage of a countermeasure or product.”

(Sec. 319L–1(a)(1)(A), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 200)

These meetings are closed to the public. While they may include participants from pharmaceutical manufacturers, distributors, and government officials, the law ensures that the details of what is discussed remain confidential:

“The Secretary shall maintain a complete verbatim transcript of each meeting or consultation conducted under this subsection. Such transcript (or a portion thereof) shall not be disclosed under section 552 of title 5, United States Code, to the extent that the Secretary, in consultation with the Attorney General and the Secretary of Homeland Security, determines that disclosure of such transcript (or portion thereof) would pose a threat to national security.”

(Sec. 319L–1(a)(1)(D), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 201)

In addition to secrecy, the law explicitly grants an exemption from antitrust laws for any participant involved in these meetings or consultations:

“Subject to clause (ii), it shall not be a violation of the antitrust laws for any person to participate in a meeting or consultation conducted in accordance with this paragraph.”

(Sec. 319L–1(a)(1)(E)(i), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 201)

Further, these private entities can enter into binding agreements that are approved by the Attorney General and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Chairman. Once approved, the agreements are also exempt from antitrust laws, even if they would otherwise limit competition:

“It shall not be a violation of the antitrust laws for a person to engage in conduct in accordance with a written agreement to the extent that such agreement has been granted an exemption under paragraph (4), during the period for which the exemption is in effect.”

(Sec. 319L–1(a)(3), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 202)

These exemptions can be renewed every three years and remain in effect unless specifically denied by the Attorney General or the FTC:

“An exemption granted under paragraph (4) shall be limited to covered activities, and such exemption shall be renewed (with modifications, as appropriate, consistent with the finding described in paragraph (4)(C)), on the date that is 3 years after the date on which the exemption is granted unless the Attorney General in consultation with the Chairman determines that the exemption should not be renewed.”

(Sec. 319L–1(a)(5), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 202)

The law also states that information obtained under these agreements cannot be used for purposes beyond what is specified in the exemption, but there is no public accountability mechanism to ensure compliance:

“The use of any information acquired under an agreement for which an exemption has been granted under paragraph (4), for any purpose other than specified in the exemption, shall be subject to the antitrust laws and any other applicable laws.”

(Sec. 319L–1(a)(7), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 203)

Congress has now extended these antitrust exemptions through September 30, 2025, allowing pharmaceutical companies and government agencies to collaborate in secrecy on the development and distribution of countermeasures, without public oversight or transparency.

Follow Jon Fleetwood: Instagram @realjonfleetwood / Twitter @JonMFleetwood / Facebook @realjonfleetwood

Section 2811A of the Public Health Service Act—Extended Federal Oversight of Children in Disasters

Congress extended Section 2811A of the Public Health Service Act through September 30, 2025. This section keeps the National Advisory Committee on Children and Disasters in operation—a federal advisory group that shapes how children are managed in declared disasters, public health emergencies, and future pandemics.

Under this law, the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), working with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), controls the appointment and oversight of the committee. Despite its benign name, this committee has broad authority to make recommendations that impact children’s medical treatment, mental health management, education, and even participation in government-run disaster drills.

The law states:

“The Secretary, in consultation with the Secretary of Homeland Security, shall establish an advisory committee to be known as the ‘National Advisory Committee on Children and Disasters.’”

(Sec. 2811A(a), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 16)

This committee isn’t just advisory in theory. Its job is to evaluate and guide government planning for how children will be treated in all types of declared emergencies—whether that’s a pandemic, bioterror event, or another disaster scenario. Its focus covers everything from mental health interventions to education policies and emergency care procedures for children.

“The Advisory Committee shall—

(1) provide advice and consultation with respect to the activities carried out pursuant to section 2814, as applicable and appropriate;

(2) evaluate and provide input with respect to the medical, mental, behavioral, developmental, and public health needs of children as they relate to preparation for, response to, and recovery from all-hazards emergencies;

(3) provide advice and consultation with respect to State emergency preparedness and response activities and children, including related drills and exercises pursuant to the preparedness goals under section 2802(b); and

(4) provide advice and consultation with respect to continuity of care and education for all children and supporting parents and caregivers during all-hazards emergencies.”

(Sec. 2811A(b), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, pp. 16–17)

The phrase “all-hazards emergencies” opens the door for this committee to insert itself into a wide range of events—whether real or perceived. This includes public health emergencies declared by HHS, which could trigger federal involvement in everything from local school closures to mass vaccination programs targeting children.

Even more concerning is the makeup of this committee. While it includes some non-federal members, it’s stacked with government officials from nearly every major public health agency—including those that pushed for pandemic lockdowns, school closures, mask mandates, and untested interventions on children during COVID-19.

The law specifies:

“The Advisory Committee... shall include the following Federal members or their designees (who may be nonvoting members, as determined by the Secretary):

(A) The Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response.

(B) The Director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA).

(C) The Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

(D) The Commissioner of Food and Drugs (FDA).

(E) The Director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).”

(Sec. 2811A(d)(3), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 18)

These are the same agencies that have been responsible for questionable pandemic policy decisions in recent years—decisions that many believe caused irreversible harm to children, including mental health deterioration, learning loss, and participation in experimental vaccination programs.

Parents have no voting power in this committee. The “parent” and “caregiver” voices included are hand-picked by the HHS Secretary. There is no requirement for public transparency on how these members are selected or who they represent.

“The Secretary shall appoint... at least 13 individuals, including...

(D) at least 4 non-Federal members representing child care settings, State or local educational agencies, individuals with expertise in children with disabilities, and parents.”

(Sec. 2811A(d)(2)(D), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, pp. 17–18)

There is no language in the law requiring public disclosure of the committee’s meetings, recommendations, or how its advice is implemented. The committee meets at least twice per year, with one required in-person meeting annually. What happens in those meetings is entirely under the control of the agencies that have already demonstrated a willingness to operate without meaningful public oversight.

“The Advisory Committee shall meet not less than biannually. At least one meeting per year shall be an in-person meeting.”

(Sec. 2811A(e), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 18)

Congress has now extended the life of this advisory committee through September 30, 2025. Without this extension, the committee was set to terminate on March 31, 2025.

“The Advisory Committee shall terminate on March 31, 2025.”

(Sec. 2811A(g), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 18)

The question is, why does a stopgap government funding bill need to extend a committee that’s tasked with developing federal strategies to manage children during national emergencies? Given the past abuses of emergency powers, extending this committee without addressing transparency or parental authority raises serious concerns about how children will be treated in the next declared disaster.

Section 2811B of the Public Health Service Act—Extended Federal Oversight of Seniors in Disasters

Congress extended Section 2811B of the Public Health Service Act through September 30, 2025. This section keeps the National Advisory Committee on Seniors and Disasters in operation—a federal advisory committee designed to coordinate how seniors are managed during declared emergencies and disasters.

Under this law, the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), working with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), controls the appointment and direction of the committee. The committee advises the government on how to oversee seniors during “all-hazards” emergencies, a broad and loosely defined category that can include everything from pandemics to natural disasters to terrorism.

The law states:

“The Secretary, in consultation with the Secretary of Homeland Security and the Secretary of Veterans Affairs, shall establish an advisory committee to be known as the National Advisory Committee on Seniors and Disasters.”

(Sec. 2811B(a), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 18)

The committee’s job is to make recommendations that affect seniors’ medical care, public health policies, and emergency preparedness plans. That includes input on how state and local governments run disaster drills and conduct emergency responses that directly impact elderly populations.

“The Advisory Committee shall—

(1) provide advice and consultation with respect to the activities carried out pursuant to section 2814, as applicable and appropriate;

(2) evaluate and provide input with respect to the medical and public health needs of seniors related to preparation for, response to, and recovery from all-hazards emergencies; and

(3) provide advice and consultation with respect to State emergency preparedness and response activities relating to seniors, including related drills and exercises pursuant to the preparedness goals under section 2802(b).”

(Sec. 2811B(b), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 19)

“All-hazards” emergencies give federal agencies sweeping authority. Once a public health emergency is declared, this committee’s recommendations can directly shape how seniors are treated—whether through lockdowns in long-term care facilities, mandatory vaccinations, or mental health interventions justified by emergency declarations.

The law also authorizes the committee to influence grant programs and cooperative agreements that fund emergency preparedness programs targeting seniors:

“The Advisory Committee may provide advice and recommendations to the Secretary with respect to seniors and the medical and public health grants and cooperative agreements as applicable to preparedness and response activities under this title and title III.”

(Sec. 2811B(c), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 19)

The committee is stacked with federal bureaucrats from multiple agencies—many of which were responsible for the catastrophic COVID-19 policies that led to widespread harm and preventable deaths in nursing homes and long-term care facilities. These are the same agencies that pushed vaccine mandates, experimental treatments, and isolation policies on seniors during the pandemic.

Federal members of the committee include:

“The Advisory Committee shall include Federal members or their designees (who may be nonvoting members, as determined by the Secretary):

(A) The Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response.

(B) The Director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA).

(C) The Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

(D) The Commissioner of Food and Drugs (FDA).

(E) The Director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

(F) The Administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

(G) The Administrator of the Administration for Community Living.

(H) The Administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

(I) The Under Secretary for Health of the Department of Veterans Affairs.”

(Sec. 2811B(d)(2), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 19)

Non-federal members are limited to a handful of health care professionals and state or local officials. Parents and families of seniors—who were locked out of nursing homes and care facilities during government-imposed restrictions—have no voice in this committee’s decision-making. The Secretary of HHS alone determines who serves.

“At least 2 non-Federal health care professionals with expertise in geriatric medical disaster planning, preparedness, response, or recovery.

At least 2 representatives of State, local, Tribal, or territorial agencies with expertise in geriatric disaster planning, preparedness, response, or recovery.”

(Sec. 2811B(d)(2)(J)-(K), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 19)

There is no requirement in the law for public transparency regarding this committee’s recommendations or its influence over federal and state policies. Meetings are mandated to occur twice a year, but there is no provision for public access to records, transcripts, or decision-making processes.

“The Advisory Committee shall meet not less frequently than biannually. At least one meeting per year shall be an in-person meeting.”

(Sec. 2811B(e), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 20)

Congress has now extended this committee through September 30, 2025. Without this extension, it was scheduled to terminate on March 31, 2025.

“The Advisory Committee shall terminate on March 31, 2025.”

(Sec. 2811B(g), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 20)

The question is, why is a temporary government funding bill extending an advisory committee that allows federal bureaucrats to dictate disaster response policies for America’s seniors? After the last public health emergency, where thousands of seniors died alone in locked facilities under questionable government policies, the lack of transparency and oversight should concern everyone.

Section 2811C of the Public Health Service Act—Extended Federal Oversight of Individuals with Disabilities in Disasters

Congress extended Section 2811C of the Public Health Service Act through September 30, 2025. This section keeps the National Advisory Committee on Individuals with Disabilities and Disasters in place—a federal committee that advises on how people with disabilities will be managed during declared emergencies and disasters.

Under this law, the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), in consultation with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), controls the committee. This body is tasked with recommending policies that impact how state and federal agencies handle disabled individuals in so-called “all-hazards” emergencies. This includes public health emergencies, natural disasters, pandemics, or bioterror events.

The law states:

“The Secretary, in consultation with the Secretary of Homeland Security, shall establish a national advisory committee to be known as the National Advisory Committee on Individuals with Disabilities and Disasters.”

(Sec. 2811C(a), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 20)

The committee’s role goes beyond offering basic advice. It has a hand in shaping emergency preparedness drills, disaster response strategies, and recovery operations at both the federal and state levels. This includes input on medical treatment, accessibility policies, and public health interventions that directly affect individuals with disabilities.

“The Advisory Committee shall—

(1) provide advice and consultation with respect to activities carried out pursuant to section 2814, as applicable and appropriate;

(2) evaluate and provide input with respect to the medical, public health, and accessibility needs of individuals with disabilities related to preparation for, response to, and recovery from all-hazards emergencies; and

(3) provide advice and consultation with respect to State emergency preparedness and response activities, including related drills and exercises pursuant to the preparedness goals under section 2802(b).”

(Sec. 2811C(b), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 20)

Once an “all-hazards” emergency is declared, federal agencies can use the committee’s recommendations to justify wide-ranging interventions—potentially including forced relocation, institutionalization, quarantine, and medical treatment mandates for individuals with disabilities. There are no clear limitations in the law on what kinds of policies this committee can influence.

The committee is made up largely of federal officials from the very same agencies that enforced some of the most draconian public health measures in recent history. These include the CDC, NIH, FDA, FEMA, and BARDA—the agencies that spearheaded lockdowns, mandates, and emergency use authorizations with little public input or oversight.

The law specifies:

“The Advisory Committee shall include Federal members or their designees (who may be nonvoting members, as determined by the Secretary):

(A) The Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response.

(B) The Administrator of the Administration for Community Living.

(C) The Director of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority.

(D) The Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

(E) The Commissioner of Food and Drugs.

(F) The Director of the National Institutes of Health.

(G) The Administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

(H) The Chair of the National Council on Disability.

(I) The Chair of the United States Access Board.

(J) The Under Secretary for Health of the Department of Veterans Affairs.”

(Sec. 2811C(c)(2), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, pp. 20–21)

There is minimal representation from non-federal individuals—and none from families or caretakers of disabled individuals unless hand-picked by HHS. The non-federal representation includes only a few health care professionals and individuals with disabilities who meet criteria determined by the government:

“At least 2 non-Federal health care professionals with expertise in disability accessibility before, during, and after disasters, medical and mass care disaster planning, preparedness, response, or recovery.

At least 2 representatives from State, local, Tribal, or territorial agencies with expertise in disaster planning, preparedness, response, or recovery for individuals with disabilities.

At least 2 individuals with a disability with expertise in disaster planning, preparedness, response, or recovery for individuals with disabilities.”

(Sec. 2811C(c)(2)(K)-(M), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 21)

Despite the scope of its influence, there is no requirement in the law for transparency. There is no mandate for public access to meeting minutes, recommendations, or transcripts. The committee is only required to meet twice per year:

“The Advisory Committee shall meet not less frequently than biannually. At least one meeting per year shall be an in-person meeting.”

(Sec. 2811C(d), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 21)

Congress has now extended the life of this committee through September 30, 2025. Without this extension, it was scheduled to terminate on March 31, 2025.

“The Advisory Committee shall terminate on March 31, 2025.”

(Sec. 2811C(g)(1), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 21)

The reality is, this committee is another example of how the federal government is embedding permanent bureaucratic control over vulnerable populations under the banner of “disaster preparedness.” After witnessing what federal agencies did to disabled individuals during COVID-19—forced isolation, denial of essential services, and coerced medical interventions—the extension of this committee without addressing transparency or accountability raises serious red flags.

Section 2812 of the Public Health Service Act—Expanded National Disaster Medical System Deployment Powers

Congress extended Section 2812 of the Public Health Service Act through September 30, 2025. This section reauthorizes the National Disaster Medical System (NDMS), a federalized response force that can be deployed anywhere in the United States during declared or potential public health emergencies.

Under this law, the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) has direct control over the NDMS, with the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) designated as its operational head. NDMS is a joint operation between HHS, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Department of Defense (DoD), and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)—allowing for a coordinated deployment of federal resources and personnel.

The law states:

“The Secretary shall provide for the operation in accordance with this section of a system to be known as the National Disaster Medical System. The Secretary shall designate the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response as the head of the National Disaster Medical System, subject to the authority of the Secretary.”

(Sec. 2812(a)(1), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 22)

NDMS is described as a “Federal and State Collaborative System,” but the reality is that the federal government determines when and where the system is deployed, including during times when no public health emergency has even been declared.

The law authorizes deployment when:

“The Secretary may activate the National Disaster Medical System to—

(i) provide health services, health-related social services, other appropriate human services, and appropriate auxiliary services to respond to the needs of victims of a public health emergency, including at-risk individuals as applicable (whether or not determined to be a public health emergency under section 319); or

(ii) be present at locations, and for limited periods of time, specified by the Secretary on the basis that the Secretary has determined that a location is at risk of a public health emergency during the time specified, or there is a significant potential for a public health emergency.”

(Sec. 2812(a)(3)(A), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 22)

This means the Secretary can deploy NDMS teams without an actual emergency declaration, based solely on a “significant potential” for an emergency.

The NDMS can be used to run federal health operations at any location the Secretary determines, with the ability to provide health services, social services, and human services, essentially establishing temporary federal control over health systems and operations in states or localities.

The law also prioritizes “at-risk populations,” which can include mandatory interventions for groups identified by federal agencies as needing “specialized and focused” public health services:

“The Secretary shall take steps to ensure that an appropriate specialized and focused range of public health and medical capabilities are represented in the National Disaster Medical System, which take into account the needs of at-risk individuals, in the event of a public health emergency.”

(Sec. 2812(a)(3)(C), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 23)

The NDMS is required to conduct mobilization exercises, including simulated bioterrorist attacks or public health emergencies affecting multiple geographic locations—laying the groundwork for multi-state federal deployments.

“During the one-year period beginning on the date of the enactment of the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act, the Secretary shall conduct an exercise to test the capability and timeliness of the National Disaster Medical System to mobilize and otherwise respond effectively to a bioterrorist attack or other public health emergency that affects two or more geographic locations concurrently.”

(Sec. 2812(a)(3)(E), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 23)

NDMS includes a federalized workforce, known as intermittent disaster-response personnel—federally appointed health workers, who are considered employees of the Public Health Service with legal immunities while deployed. This workforce can be expanded at will if the Secretary declares a shortage.

“For the purpose of assisting the National Disaster Medical System in carrying out duties under this section, the Secretary may appoint individuals to serve as intermittent personnel of such System in accordance with applicable civil service laws and regulations.”

(Sec. 2812(c)(1), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 24)

These personnel are shielded from liability under federal law and can be deployed for “training programs” as well as emergencies:

“With respect to the participation of individuals appointed under paragraph (1) in training programs... acts of individuals so appointed that are within the scope of such participation shall be considered within the scope of the appointment...”

(Sec. 2812(c)(2), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 24)

If the Secretary decides there aren’t enough personnel to handle a public health emergency or even the potential for one, they can bypass traditional hiring practices and directly appoint individuals to NDMS positions. There is no limit on how many appointments can be made or the criteria for such appointments.

“If the Secretary determines that the number of intermittent disaster response personnel within the National Disaster Medical System under this section is insufficient to address a public health emergency or potential public health emergency, the Secretary may appoint candidates directly to personnel positions for intermittent disaster response within such system.”

(Sec. 2812(c)(4)(A), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 24)

The federal government has also established agreements with states and private entities to use federal equipment and assets, even when NDMS has not been formally activated by HHS. This raises concerns about federal encroachment on state sovereignty and the blending of public and private control during emergencies.

“The Secretary shall establish criteria regarding the participation of States and private entities in the National Disaster Medical System... which may in the discretion of the Secretary include authorizing the custody and use of such property to respond to emergency situations for which the National Disaster Medical System has not been activated by the Secretary...”

(Sec. 2812(b)(3)(A), PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE ACT, p. 24)

Congress has now extended the NDMS’s enhanced authorities through September 30, 2025. Without this extension, the expanded authorities over NDMS were set to expire on March 31, 2025.

Follow Jon Fleetwood: Instagram @realjonfleetwood / Twitter @JonMFleetwood / Facebook @realjonfleetwood

Trump's CDC, FDA 'Actively Participating' in WHO Bird Flu Seminar Despite Executive Order to Withdraw U.S. from International Organization: STAT

The U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are “actively participating” in virtual meetings with the World Health Organization (WHO) at the Crick Worldwide Influenza Center in London.

New 116-Page Stop-Gap Bill Hides Renewed Emergency Powers Extended to 2025

Summary: The shorter, 116-page version of the 1,547-page stop-gap spending bill unveiled Tuesday night includes provisions that quietly extend government emergency powers under the Public Health Service Act (PHSA) (here) to March 31, 2025. Notably, the bill does not specify what these sections entail—an alarming omission given the sweeping powers they g…

Congress to Fund New Biolab Construction, Deadly Pathogen Research, Coming Influenza Pandemic, Vaccines: Speaker Johnson’s New 1,500-Page Spending Bill

In a new spending bill first seen last night, the United States government is looking to bankroll the construction of new biolabs, risky experiments on dangerous pathogens, vaccines, and the coordination of an apparently incoming influenza pandemic.

Australian Gov't Abused Human Rights During COVID-19 Pandemic: Australian Human Rights Commission

Australia’s own Human Rights Commission (AHRC) has issued a damning verdict on the country’s pandemic response, confirming what many Australians already knew: government policies during COVID-19 caused catastrophic harm to human rights and disproportionately devastated the nation’s most vulnerable.

Very disappointing that Trump is promoting this shit CR.

Rep. Thomas Massie is entirely correct. The CR should be voted down, the genocidal pharma-licking parts removed, and the budget actually reduced instead of increased yet again.

Awful! What is there to do against these seeping powers of theirs? "This raises concerns about federal encroachment on state sovereignty and the blending of public and private control during emergencies," in other words, fascism!